The telegraph and business invasions of privacy

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

February 2011

500 words / 3 min.

Tweet

Share

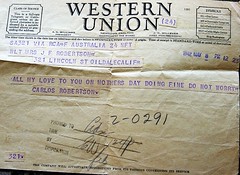

In the late 19th century, many began to see the rise of monopolistic telegraph operators as more of a threat than the government. Against this potential eavesdropper, the Bill of Rights provided no protection.

Please note that this post is from 2011. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

The applicability of the Fourth Amendment to telegraphic communications in the late nineteenth century may have been disputed, but it was at least defensible. Many, though, began to see the rise of monopolistic telegraph operators as more of a threat than the government. Against this potential eavesdropper, the Bill of Rights provided no protection. As David Seipp notes, “Constitutional protections against search and seizure … were designed to protect the privacy of individuals from invasion by government, not business.”

In the 1870s, in the face of increasing government pressure, the president of Western Union, William Orton, strongly maintained the importance of protecting the confidentiality of telegraphs as foundational to his business, arguing that customers had “reposed in us the gravest confidence concerning both their official and their private affairs.”

By the 1880s and 1890s, in the face of rising “robber barons” and business monopolies, business began to be seen by the public as more of a threat to privacy than the protector of privacy. Wall Street financier Jay Gould united the entire telegraph system into one monopoly in 1881, and was widely believed to monitor telegraphic communications to increase his wealth and investments.

Laws in the nineteenth century generally provided little or no protection from wiretapping and similar activities by private individuals, except through application of laws against trespass. Thus, third-parties tapping into Western Union lines could be prosecuted, but Western Union itself was limited only by its own rules and regulations from such monitoring.

Western Union successfully defeated federal laws against government “intrusion” (regulations or the “postalization” of the telegraph) into their monopoly until the early twentieth century, when the telegraph began to be eclipsed by the telephone.

At the state level, however, some protections against the disclosure of private messages by telegraph operators did exist, albeit in a patchwork form throughout the country. Even without specific laws, suits charging improper disclosure were successful at the state level, provided monetary loss could be demonstrated.

By the end of the nineteenth century, a right to privacy focused mostly on the inviolability of the home had been extended, at least in legal discourse and the popular imagination, to extra-domicile communications. While the extension of the Fourth Amendment to electr(on)ic communications would have to wait until Katz and Berger in the mid-twentieth century, the stage had been set for change by the new technology of the telegraph.

For more discussion of privacy in America and the law, see David Seipp, The Right to Privacy in American History, pp. 77-95 (1977-78).

Related articles

- Extending the Fourth Amendment beyond the home: Ex parte Jackson (1878) (inpropriapersona.com)

- You: Cautionary lessons in history of information technology (washingtonpost.com)

- Stepping stone to Internet privacy: the telegraph (inpropriapersona.com)