Were telegrams privileged communications?

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

April 2011

1400 words / 7 min.

Tweet

Share

With the introduction of the telegraph in the 1800s, some jurists, recognizing the growing importance of telegraphic communication, advocated for a kind of “telegraph operator-customer” privilege.

Please note that this post is from 2011. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

Under the common law, a “privilege” shields communications between certain people from being introduced as evidence in court. Some examples include spousal privilege, attorney-client privilege, and priest-penitent privilege. These privileges are generally created to serve a greater public good, and exist because, on balance, the courts (or legislatures) feel that protecting the confidentiality of certain communications overall is better than requiring their revelation in specific instances.

Under the common law, a “privilege” shields communications between certain people from being introduced as evidence in court. Some examples include spousal privilege, attorney-client privilege, and priest-penitent privilege. These privileges are generally created to serve a greater public good, and exist because, on balance, the courts (or legislatures) feel that protecting the confidentiality of certain communications overall is better than requiring their revelation in specific instances.

With the introduction of the telegraph in the 1800s, some jurists, recognizing the growing importance of telegraphic communication, advocated for a kind of “telegraph operator-customer” privilege. Doing so would foster this new communication medium, since using it required divulging potentially confidential information to the telegraph operators. This approach failed, and a new one, relying on the Fourth Amendment, failed to take hold before telegrams lost their special place in American life.

Michigan, 1860

As early as 1860, a justice of the peace in Michigan jailed a telegraph operator who refused to turn over telegrams relevant to a murder investigation, arguing that such communications were privileged.

The attorney for the operator argued before the Michigan Supreme Court in In Re Farnham, 8 Mich. 89:

That communications intrusted to an operator for transmission by telegraph, as well as those received by him for delivery, are confidential, and he is not at liberty to disclose them: Comp. L., §§ 2064, 5912. The justice has no right to require the disclosure of communications which the law says he shall not disclose. Compare the provisions with respect to ministers and physicians: Comp. L., §§ 4322, 4323; Johnson v. Johnson, 4 Paige, 460.

The reason why the statute prohibits the telegraph operator from disclosing the communications, is the same as in the case of attorneys, ministers and physicians–that of public policy; the idea that on the whole more good will result to the people generally by the prohibition and immunity than without it. And no good reason for the rule can be urged in the case of attorneys, physicians and ministers, that does not apply with equal if not greater force to the case of telegraph operators.

In the end, though, the Michigan Supreme Court decided the question would be “improper for the court to pass upon,”since they decided the “examining magistrate” could not commit someone for refusing to testify anyway, thus neatly sidestepping the privilege question

Maine, 1870

Another state supreme court, this one in Maine, was faced with a similar argument about the potential for granting privilege to telegraphic communications in 1870 (State of Maine v. Alden Litchfield, 58 Me. 267). The defendant argued for privilege, but the court disagreed, saying that:

a verbal message … would be admissible. The mode of transmission to the person delivering the message, whether by telegraph or otherwise, has nothing to do with the matter. … Nor can telegraphic communications be deemed any more confidential than any more confidential than any other communications. …

The court goes on to say, “The honest man asks for no confidential communications, for the withholding of same cannot benefit him. The criminal has no right to demand exclusion of evidence because it would establish his guilt.” In short, the “telegraphic operator, as such, can claim no exemption from interrogation.”

West Virginia, 1874

Similar in its holding if not its logic, the West Virginia Supreme Court, in National Bank v. National Bank, 7 W. Va. 544 (1874), decided not “to approve the doctrine that … telegraphic communications are privileged from disclosure,” noting that while “[l]etters passing through the mail are protected by an act of Congress from being seized and opened for the purpose of furnishing testimony,” the same was not true of telegrams. Adopting the new “privilege” would “limit the field of inquiry after truth,” and doing so should be left to the legislature, not the courts, since it was “unknown to the common law.”

Federal Court, Missouri, 1876

In United States v. Babcock, 24 F. Cas. 908 (1876), a federal court held that, despite Western Union’s attempt to quash, the broadly written subpoena ordering them to produce telegrams was valid and binding, since it “describes, with sufficient particularity, indeed, with all the particularity that seemed to be practicable, under the circumstances, the very messages that are wanted.” The court made no reference to the Fourth Amendment, only to the common law of subpoenas.

No argument was made concerning privilege per se, and thus the court did “not consider whether there is any ground to suppose that, in law, the telegraph company occupies a different relation than would be occupied by private persons having custody of the same papers.”

Missouri, 1880

Citing State v. Litchfield in 1880, the Missouri Supreme Court in Ex parte Brown held that “[t]elegraphic messages are not privileged communications.” Echoing Litchfield, the court added, “There is no statute of this State or principle of law which places a telegram on a different ground from that which any other communication occupies, made by one through another, to a third party.” The court decided that the “only ground … upon which the exemption of telegrams from this process of the court can be placed, is that they are privileged communications, and we cannot declare them to be such in the absence of a statute so providing.”

Additionally, the court acknowledged that telegraph companies are “subjected to a penalty for disclosing the contents of any private dispatch,” but noted that this restriction did not apply “in a judicial proceeding.”

However, unlike others of its contemporary courts, the Missouri Supreme Court went beyond a discussion of privilege, and examined the possibility that the Fourth Amendment (or, rather, the state equivalent) might indeed protect telegraphic communications, at least inasmuch as to require that the messaged to be produced must be “described with sufficient accuracy.” Before proceeding with this analysis, the Missouri Supreme Court rejected the lower court ruling that the analysis under the state equivalent of the Fourth Amendment “has but little bearing on the present question.”

Instead, the Missouri Supreme Court held that the order to produce the telegrams was overly broad, and did not meet the requirements of the state equivalent of the Fourth Amendment. As part of this holding, they rejected Babcock, and required a higher standard of specificity than that lower federal court. The logic of their arguments is quite similar to those of the the 1878 United States Supreme Court decision when it protected postal mail in Ex parte Jackson (although the Missouri Supreme Court did not cite to Jackson, although the petitioner did). In the end, then, they quashed the subpoena.

Federal Court, New York, 1883

In the 1883 case of Wertheim, a federal court in New York agreed with Ex parte Brown’s approach to privilege when it summarized the law as follows:

On the ground of privileged communications it has been attempted by the officers of telegraph companies to withhold copies of dispatches in their hands when required as evidence in courts of justice. This attempt, however, has not succeeded. It is held that telegraph messages in the hands of officers of the company are not privileged communications; and they must be produced when ordered by a subpoena duces tecum, any rule or by-law of the corporation to the contrary notwithstanding.

The federal court made no reference to the Fourth Amendment. It explicitly followed Babcock in allowing broad subpoenas, provided they met certain limited standards of minimal specificity.

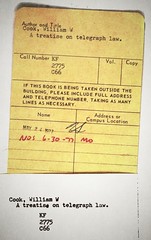

A Treatise on Telegraph Law, 1920

By 1920, the question on privilege appeared firmly settled, and the Missouri Supreme Court’s arguments regarding search and seizure seemed essentially lost:

A telegraph company is not privileged as to messages transmitted by it; but on the other hand, such messages are not to be made public by the telegraph company. (William W. Cook , A Treatise on Telegraph Law, 203)

Related articles

- An argument for the “Inviolability of Telegraphic Correspondence” (inpropriapersona.com)

- The Fourth Amendment: from property to people (inpropriapersona.com)