New-Fashioned Quarantine (from 1916)

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

October 2014

500 words / 3 min.

Tweet

Share

One traditional method Hill discusses is quarantine – but Hill gives it a rational spin, characteristic of early twentieth century optimism and trust in science and expertise.

Please note that this post is from 2014. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

In 1916, Herbert Winslow Hill published The New Public Health, an attempt to update old ideas about public health — focused on the efforts of “sanitarians” to push “cleanliness,” even as the formerly standard “miasma” theory of disease was supplanted, at the individual, home, and city level — and replace it with methods that targeted the transmissions methods of specific diseases.

He emphasizes throughout that only specific kinds of “dirt” and specific carriers of diseases are the problem, and that effectively countering the spread of disease requires rational targeting of these problems.

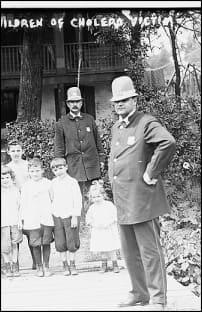

One traditional method he discusses is quarantine — but Hill gives it a rational spin, characteristic of early twentieth century optimism and trust in science and expertise. Old-fashioned quarantine, he says, took only “part of the infected, and also took the well with the sick” (190-91).

Thus, not alone were many infected persons overlooked and many uninfected persons wrongly held, but also the disease spread oftentimes from those infected who were in the net to the uninfected who were kept in with them, so that old fashioned quarantine, while it protected the community but partially, meant often poverty, disease, and death to those caught in its toils. No wonder the very name of quarantine makes many people shudder. (191)

“New-fashioned quarantine,” on the other hand, “is not a blanket method” (191). Instead, “it requires definite detailed knowledge applied with care and patience, not mere force” (191).

Hill argues that it is not quarantine itself that people find unjust, but rather the unjust application of it — “the thing that chafes and riles the average person is not restriction but unjust restriction”– and this can be corrected “through the methods of epidemiology, of the laboratory, and of the vital statistician, skilfully combined by experts” (192).

Concerns about individual rights and the autocratic authority of the state are thus effectively dealt with through a fair and just application of reason:

Set all others free, but keep these persons, not in old-fashioned quarantine, but under such control that their discharges will not pass to others; and do not measure the length of that control by fixed time limits, blind and unjust as quarantine itself, but measure it wholly by the length of time the germs remain in or on the body. The moment that the germs have left those persons they are no longer harmful and they should be freed. (192)

Thus, the solution to social resistance is solved through what might be called “procedural due process,” backed up by scientific evidence and “men who know their business and do nothing else”; if started immediately, the end result would be, according to Hill, that “infectious diseases in ten years would have vanished and would have become mere history” (192).