Sex and Eugenics Sterilization

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

October 2014

700 words / 4 min.

Tweet

Share

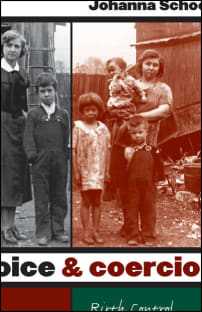

In looking through Johanna Schoen’s 2005 book, Choice & Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare, it appears that, although eugenics-based sterilization procedures in the early-to-mid twentieth century appear to have targeted women more than men, men were also sterilized through these programs.

Please note that this post is from 2014. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

In looking through Johanna Schoen’s 2005 book, Choice & Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare, it appears that, although eugenics-based sterilization procedures in the early-to-mid twentieth century appear to have targeted women more than men, men were also sterilized through these programs.

Rationally, it should be unsurprising that men were targeted as well: the basic eugenics justification for sterilization applied equally to men as well as women (in fact, since an individual male is able to produce many more children than an individual female, sterilization might, on a purely rational basis, even be considered more critical for men than for women). Nonetheless, my readings so far on the subject strongly suggest that so-called “eugenics boards” targeted women more often.

Thus, in practice, particularly when applied by these non-scientific “eugenics boards” — local committees charged by state laws with sterilization decisions — women were targeted more often than men: “Sixty-one percent of eugenic sterilizations nationwide and 84 percent in North Carolina were performed on women,” according to Schoen (95). “Feeblemindedness” was associated by eugenics scientists with sexual promiscuity; eugenics boards treated sexual promiscuity as essentially a proxy identifier of “mental defects” (94-95). And since “promiscuity” was especially identified as a problem for women outside of marriage, these individuals became “the main target of sterilization programs” (95).

Commonly, especially as eugenics boards became tied to welfare programs, pregnancy and the poverty that often accompanied it became the problem that sterilization proponents targeted, even if they still couched their decisions in terms of “feeblemindedness” and heredity. Since a pregnancy outside of marriage provided a visible sign of promiscuity and mental defectiveness, women were easier to identify as potential sterilization targets than men, contributing as well to the unequal rates of sterilization.

Still, when identified, men also became targets for sterilization, although not always for good reasons. Thus, eugenics boards wished to sterilize “sexually aggressive men” not necessarily because it would stop attacks on women, but rather “so that if [they] made an attack [they] would be harmless” — because the potential harm to society came not from the “physical or psychological harm it caused its victims, but rather in the possibility that it might cause pregnancy” (102).

Some sterilization proponents may indeed have been more interested in reducing burdens on society created by pregnancies outside of marriage. Others, however, may not have understood what the effects of sterilization would be, and may have, logically or not, seen it as protection against abuse: “In the imagination of parents and social workers … sterilization promised much more than it could deliver” (101). Some parents saw it a possible cure for mental problems, others as protection against rape and incest (101-02). But the result was to render “illicit and unwanted sexuality invisible” (102).

Before the 1950s, men seem to have been targeted more often for sterilization than in later decades, possibly because of ease of identifying the institutionalized “feebleminded,” male or female. Thus, “Patrick,” a nineteen-year old male inmate of the Caswell Training School —- identified as having an “IQ of thirty-nine” and considered to be “a sex problem” — was sterilized in 1943, while his ten-year old sister was not (87). The ability of directors of mental institutions, as well as social workers, to submit sterilization petitions, facilitated this identification and targeting of the institutionalized,

By the 1950s, after eugenic science had been largely discredited, involuntary sterilization programs grew, particularly in certain states where they were tied to an increase in welfare rolls (108). Pregnancy-based identification of candidates for sterilization, justified on the basis of reducing welfare burdens and initiated by social workers, targeted women vastly more often than men. Additionally, non-discrimination requirements in welfare disbursement, along with other societal shifts, resulted in a growing association between fertility and non-white women, in particular (108-09). Black mothers, in particular, were blamed for “urban plight, poverty, and social unrest,” and were correspondingly targeted for sterilization (109). The possibility of sterilizing men, black or white, was apparently ignored.