An argument for the “Inviolability of Telegraphic Correspondence”

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

April 2011

1000 words / 5 min.

Tweet

Share

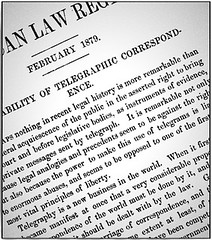

Former Michigan Supreme Court Justice Thomas M. Cooley, in a forward-looking article, advocated for extending Fourth Amendment protections to telegrams in 1879. Cooley articulated a position that both foreshadowed 20th century arguments over telephone wiretaps, and reflected his late 19th century concerns.

Please note that this post is from 2011. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

Former Michigan Supreme Court Justice Thomas M. Cooley, in a forward-looking article, advocated for extending Fourth Amendment protections to telegrams in 1879. Cooley articulated a position that both foreshadowed 20th century arguments over telephone wiretaps, and reflected his late 19th century concerns.

Former Michigan Supreme Court Justice Thomas M. Cooley, in a forward-looking article, advocated for extending Fourth Amendment protections to telegrams in 1879. Cooley articulated a position that both foreshadowed 20th century arguments over telephone wiretaps, and reflected his late 19th century concerns.

Cooley’s “Inviolability of Telegraphic Correspondence” advocated for protecting correspondence sent via this relatively new technology from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” As support, Cooley turned first to the influential English case of Entick v. Carrington, in which English government agents entered a private domicile and seized private papers. Cooley writes:

The case [Entick], as will be seen, did not by any means turn wholly upon the breaking into the tenement and the forcing of locks, but it brought to the front as a principal grievance the injury the subject might sustain by the exposure of his private papers to the scrutiny and misconception of strangers.

The key for Cooley–unlike some other commentators–was the “exposure of … private papers to the scrutiny and misconception of strangers.” For Cooley, telegrams are exactly the same as private papers, and should be available for use as evidence only in regards to the telegraph company (which has a “qualified property interest in them”), the sender, and the receiver. He analogized telegrams to postal mail, where “every invasion of it [the post] has been punishable” (though the Supreme Court only explicitly gave Fourth Amendment protection to postal mail the year before Cooley’s article, it did so based on a long-standing understanding that postal mail ought to be inviolable).

Telegraphic communications were protected to some degree by state law, but above all by company regulations (i.e., essentially contract law) formulated to encourage citizens to entrust their correspondence to the telegraph company:

For the most part telegraph companies were left to make rules and regulations to govern their own business. … The most important regulation which has been established by statute is that inviolable secrecy shall be preserved in respect to messages by those through whose hands they shall pass; severe penalties being imposed upon operators who violate this injunction.

Cooley wished to extend constitutional protection to telegrams, “by those maxims of the common law by which individual liberty is guarded and protected.” But he found no “express provision of the Constitution” by which to do this, although he uses the language of the Fourth Amendment, and looked instead to “previous history in the light of which constitutions must be interpreted.”

Despite relying on Entick, which dealt with an agent of the state, Cooley, foreshadowing Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis, is less concerned with state surveillance than he is with private abuses. Cooley frames his worries in terms of protection against “competitors and gossips”:

Telegraphic communication, if not inviolable, offers a perpetual temptation to malice. A legislative committee may employ the power of calling for it to blacken the reputation of an opponent; a business rival may be annoyed and perhaps seriously compromised by means of it; a family feud may be avenged or quickened by bringing out confidential messages, and so on.

In this sense, Cooley’s approach, while suggestive of 20th century extensions of the Fourth Amendment, reflects 19th century concerns. Communication was becoming more rapid, and newspapers–along with gossip columns–were booming. The federal government had limited powers, and modern police forces were only just developing.

Despite similarities, Cooley’s view is distinct from Warren and Brandeis’. As Neil Richards and Daniel Solove, in “Privacy’s Other Path: Recovering the Law of Confidentiality” suggest about Americans pre-1890, what Cooley seemed more concerned with was the confidentiality of material entrusted for transit between people, not with the secrecy accorded to private materials intended for one’s own use. Cooley was concerned with the revelation of private correspondence, not with protecting the sanctity of the individual (in contrast to Warren and Brandeis). Cooley argued against

the right to compel the telegraph authorities to produce private messages which, by the course of the business are necessarily left in their possession, but under a confidence imposed by the law [or by company regulation].

Cooley’s ideas, though still clearly enmeshed in 19th century concerns, prefigure 20th century understandings of the Fourth Amendment. Cooley, for example, believes that it should make no difference where the private correspondence was stored–the potential damage and exposure are equal:

If one’s private correspondence is to be given to the public, the method is not important; it is equally injurious whether done by sending an officer to force locks and take it, or by compelling the person having the custody to produce it.

In short, argues Cooley, what is the difference between papers stored in the home and correspondence held at a telegraph office? This idea is not dissimilar to the majority opinion in Katz v. United States that the “Fourth Amendment protects people, not places.” In Cooley’s view, if a person’s correspondence is open to seizure in a telegraph office, then why should it be more protected in his home?

And if a search in a telegraph office and a seizure of a man’s private correspondence is not an unreasonable search and seizure, on what reasons could the search for and exposure of his private journals be held to be an invasion of his constitutional right?

Related articles

- The Fourth Amendment: from property to people (inpropriapersona.com)

- Law of privacy vs. confidentiality in the nineteenth century (inpropriapersona.com)

- Extending the Fourth Amendment beyond the home: Ex parte Jackson (1878) (inpropriapersona.com)