Warrantless wiretaps and the Fourth Amendment: why would a court allow a violation of the Constitution?

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

August 2012

700 words / 3 min.

Tweet

Share

In Appeals Court OKs Warrantless Wiretapping, David Kravets summarizes a recent 9th Circuit decision regarding wiretaps by the federal government. How is this possible?

Please note that this post is from 2012. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

In Appeals Court OKs Warrantless Wiretapping, David Kravets summarizes a recent 9th Circuit decision regarding wiretaps by the federal government:

In Appeals Court OKs Warrantless Wiretapping, David Kravets summarizes a recent 9th Circuit decision regarding wiretaps by the federal government:

The federal government may spy on Americans’ communications without warrants and without fear of being sued, a federal appeals court ruled Tuesday.

But how is this possible, if the Supreme Court has already ruled (in Katz v United States) that wiretaps without warrants violate the Fourth Amendment?

First, let’s go back and review what the Fourth Amendment says:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Per usual in looking at the United States Constitution, the general idea here is clear, but the particulars are not. What does “secure” mean? How do “Warrants” related to security? What’s the role of the judiciary in this process? And perhaps most critically: what do we do about a violation?

The courts, faced with this kind of ambiguity, have decided that the most powerful enforcement mechanism is to exclude evidence gathered in violation of the Fourth Amendment from all criminal prosecutions — regardless of guilt or innocence of the parties. Beyond this, the courts rely on the legislature (Congress, in the federal system) to provide additional mechanisms of enforcement.

Of course, civil lawsuits alleging harm are a traditional, “bottom-up” way for citizens to leverage the court system to address grievances. So even without clear mechanisms granted by Congress, why can’t our common-law system build on traditional torts like trespass to enforce the Fourth Amendment?

The answer to that involves a very old doctrine known as sovereign immunity. The old idea the United States inherited was the the King (sovereign) created the Courts, and therefore they could not be used against him. Article III, Section 2 is one possible Constitutional source for federal soverieign immunity, while the Eleventh Amendment has been held to protect states. But as with many things, sovereign immunity is more deeply rooted in judicial tradition — i.e., common law — than it is in the specific words of the Constitution. 200 years+ of sovereign immunity as a core principle of the American legal system means that it will take more than a trial court to change.

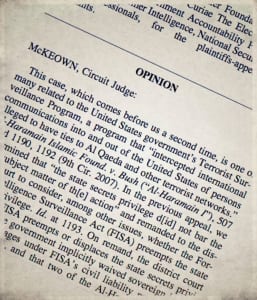

While Congress could waive sovereign immunity entirely, it never has. Instead, Congress has waived sovereign immunity and allowed suits against the government only in specific types of cases — and thus the key question in AL-HARAMAIN ISLAMIC v. OBAMA is whether Congress has or has not waived immunity in the case of wiretaps. The Ninth Circuit says the answer is that Congress has not waived:

The threshold issue in this appeal is whether the district court erred in predicating the United States’ liability for money damages on an implied waiver of sovereign immunity under § 1810. It is well understood that any waiver of sovereign immunity must be unequivocally expressed. Section 1810 does not include an explicit waiver of immunity, nor is it appropriate to imply such a waiver.

In essence, the court cannot even consider the merits of the case, because the federal government is immune from suit. In short, citizens can only enforce the Katz and the Fourth Amendment restriction on warrantless wiretaps through political action (i.e., Congressional legislation), not through the courts.

All that said, the courts — per the Exclusionary Rule — will not allow evidence gathered in this way to be used in court, and might also order someone held on the basis of this evidence released in a habeus corpus petition. But without the authorization of Congress, citizens cannot sue for this violation of the Bill of Rights.

Relevant cases

- katz v. united states, 389 u.s. 347 (1967)

- charles katz v. united states, 386 u.s. 954 (1967)

- united states v. united states dist. court for eastern dist. of mich., 407 u.s. 297 (1972)

- terry v. ohio, 392 u.s. 1 (1968)