History and its purpose: the case of the government and the Internet

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

July 2012

1300 words / 6 min.

Tweet

Share

The purpose of history is to provide a mildly depressing, reality-based narrative that helps guide future decisions.

Please note that this post is from 2012. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

I have written before on underdetermination: that in many cases, the same data can produce many “right” answers (but at the same time, not any answer is equally valid). Thus, for example, without bringing in additional support, the U.S. Constitution does not by itself definitely answer the question of whether or not GPS tracking is a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

To help answer this kind of question — and many other public policy questions — many of us turn to history (or sociology, or political science, or similar disciplines) to provide further evidence to help choose between equally rational arguments. The purpose of history is to provide a mildly depressing, reality-based narrative that helps guide future decisions.

History is of course too vast and detailed a source of evidence to utilize in full (how do we incorporate the experiences of everyone who has ever lived into our analysis?). Still, the data it provides can help us bolster one aspect or another of an otherwise underdetermined argument.

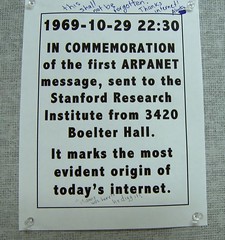

It should be no surprise then, that history should be invoked again to help answer the question of the role of government in society. More specifically, does — or can — government actually help innovation and development, or is it all due to the heroic efforts of individuals working within private enterprises? Asking if government can develop technologies is essentially a historical question, since development happens over time — and that’s history. So it should be no surprise that conservatives seeking evidence to support their proposition that government is the enemy of innovation should turn to history for data.

But what happens when this history is wrong?

On the WSJ opinion page, Gordon Crovitz, in “Who Really Invented the Internet?,” maintains:

Contrary to legend, it wasn’t the federal government, and the Internet had nothing to do with maintaining communications during a war.

Crovitz answers his title’s question by giving credit to private enterprise instead of government:

If the government didn’t invent the Internet, who did? Vinton Cerf developed the TCP/IP protocol, the Internet’s backbone, and Tim Berners-Lee gets credit for hyperlinks. … But full credit goes to the company where Mr. Taylor [who had worked previously for the Department of Defense] worked after leaving ARPA: Xerox.

Crovitz thus provides evidence from history to undermine an argument that government can be responsible for innovation — a perfectly valid use of history to escape the limitations of arguments about the static state of affairs we see around us at any one moment. Unfortunately, his history is simply wrong. While there is, as I noted above, so much history available that any reporting of it is inevitably selectionist and limited, that (like with underdetermination of the Constitution) does not mean that any selection of historical facts is equivalent to any other. Sometimes you are just wrong.

In the case of Crovitz’s article, the power of the press came quickly to bear on the issue. A variety of writers — including Michael Hiltzik, cited by Crovitz in support of his argument — disagree with much of the evidence Crovitz uses to support his argument. Hiltzik writes in the Los Angeles Times:

And while I’m gratified in a sense that he cites my book about Xerox PARC, “Dealers of Lightning,” to support his case, it’s my duty to point out that he’s wrong. My book bolsters, not contradicts, the argument that the Internet had its roots in the ARPANet, a government project.

Ars Technica writer Timothy B. Lee rebukes Crovitz in an article called, “WSJ mangles history to argue government didn’t launch the Internet.” In “Yes, Virginia, the Government Invented the Internet,” PC Magazine writer Damon Poeter adds, reiterating Hiltzik’s point, that

Crovitz wants to somehow credit private industry for the invention of the TCP/IP communications protocol without acknowledging that Vinton Cerf and Robert Kahn developed it on a government contract.

Then drawing on this revised evidence, Michael Moyer, the editor in charge of technology coverage at Scientific American, concludes:

In truth, no private company would have been capable of developing a project like the Internet, which required years of R&D efforts spread out over scores of far-flung agencies, and which began to take off only after decades of investment. Visionary infrastructure projects such as this are part of what has allowed our economy to grow so much in the past century. Today’s op-ed is just one sad indicator of how we seem to be losing our appetite for this kind of ambition.

Now, Moyer’s conclusion is not the only one possible, even from the revised evidence of early Internet history. Based on the shared historical evidence we know all have, it might be equally rational to argue that the Internet was an exceptional case, that in general innovation doesn’t work this way, or even that everything would have gone better or faster if government had just stayed away. This is where the debate should be — but it’s an impossible debate to have when the evidence is wrong.

Fortunately, the Internet was developed recently enough that many people were there, and can correct bad history. Also fortunately, the medium of press dissemination is the Internet, and thus there are many interested and widely read researchers who can correct the record. But so many other (mis-)uses of history lack this kind of capable and effective cadre of fact checkers, and it is left to the general public to sort through and evaluate facts and evidence themselves (and of course, even the most capable researcher or historian often reads outside of their field of knowledge). What do we do about this?

- First, of course, writers need to take on the individual responsibility to check their facts and confirm their evidence — and to try, within their available abilities, to avoid evidence drawn from conclusions rather than conclusions drawn from evidence.

- Second, readers should act responsibility: think critically, evaluate sources, and confirm (as much as possible) the evidence.

- Third, historians need to accept that we have a role to play in society, whether we like it or not — and to recognize the importance of our work outside of the academy.

- Fourth, society as a whole should recognize the importance of history and the key role historians play in providing the evidence to make informed and responsible public-policy decisions.

It’s naïve to expect historians to be unbiased. Doing history requires selectivity, and good historians draw reasonable conclusions from their work. But ethical historians (and thinkers generally) don’t mold their evidence to fit their world-views, even if their world views do (always) influence their work. There’s nothing wrong with using historical evidence to make a point — that’s an important part of public-policy analysis — but manipulating evidence undermines the validity of analysis and undermines public trust.

There are more purposes to history that facilitating public-policy decisions. But this is one key purpose of history, and its one we should all keep in mind when doing history (whether we are professionals or not). Stated too simply: good history illuminates; bad history deceives. It’s naïve to think, of course, that good history will really solve anything — but bad history certainly won’t help!