David Seipp on Themes of the Nineteenth-Century Rhetoric of Privacy

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

October 2014

800 words / 4 min.

Tweet

Share

In his late 1970s work, The Right to Privacy in American History, David J. Seipp argues that the “unity of the privacy phenomenon” in the nineteenth century came not from a singleness of motive, but rather from “a unity of language” (Seipp 116).

Please note that this post is from 2014. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

In his late 1970s work, The Right to Privacy in American History, David J. Seipp argues that the “unity of the privacy phenomenon” in the nineteenth century came not from a singleness of motive, but rather from “a unity of language” (Seipp 116).

Sanctity

The “recurrent idea of sanctity” is the first theme noted by Seipp (116-17). He suggests that the “common source” of the theme “was the ascription of sanctity to letters in the post office,” citing Francis Lieber’s book on civil liberty from 1853 and a New York Times article from 1858 (117-18).

As the century progressed, writers analogized telegrams to letters, and argued that too deserved “inviolable sanctity” in the face of, for example, congressional subpoenas (117).

Later, as the census expanded in scope and details, objectors “sanctified … matters of debt and disease,” citing King David’s troubles when “number[ing] his people” (117)

The “sanctity of private life” was contrasted with the practices of newspaper reporters and photographers too, in articles from 1876-1903, including Warren and Brandeis’ famous 1890 law review article on privacy (117). Even biographers were faulted in the 1880s for “violating ‘the sacred recesses of saintly lives'” and “the ‘sacredness of personality'” (118).

Other zones of private life also became sanctified in the late nineteenth century (118). Childbirth, for example, was “most sacred,” according to Seipp’s citation to an 1881 case in which a court in Michigan held that a woman has “a legal right to the privacy of her apartment” (118). Critics of the proposed income tax argued that financial matters were some of “those affairs of the individual which were in a sense sacred” (118).

Domesticity

The “rhetoric of domesticity” was deeply entwined with that of sanctity. Seipp traces the legal origins to the “British legal proverb, ‘A man’s house is his castle'” (119). The New York Times emphasized the maxim when discussing census-taking in 1875, and the Tribune did so in 1877 when it compared “searches of houses to searches of private telegrams” (119).

According to Seipp, the rhetoric connected to “two key concepts — private property and familial privacy” (120). The “right to quiet and exclusive enjoyment of property” emerged early on in America, and property considerations continued to animate “many assertions of a right to privacy” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (120).

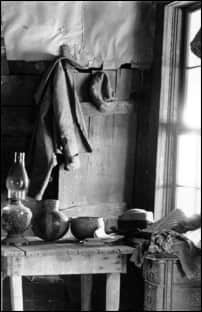

But the most potent formulation of privacy and property came not in regards to “just any piece of real estate, but specifically to the home and to home life” (120-21). Sepia cites social historian David Kennedy’s 1975 work to suggest that urbanization and industrialization, plus the Civil War and territorial expansion, led to a greater sense of familial privacy” (121).

Individualism

Seipp argues that the “inviolable personality of the individual” comprised the third, and likely most important, “major theme of late nineteenth century privacy rhetoric” (121). Cooley, who wrote influential legal treatises and advocated for protecting telegrams as if they were postal letters, wrote that the “right to one’s person may be said to be a right of complete immunity; to be let alone” (121), heavily influencing Warren and Brandeis’ “right to privacy” (121). Sepia connects this to arguments for a “right to reputation” directed against newspapers as well (121-22). In discussing the “American habit of respect for the personality and the reputation of private citizens” in citing William James’ 1890 book on psychology and his praise of “the well-known democratic respect for the sacredness of individuality” (122).

Relatedly, but even more importantly, says Seipp, was the relationship of the rhetoric of privacy “to legal traditions of personal rights — similar to the relationship of rhetoric concerning domesticity to traditions of property rights” (123). In fact, Seipp says, the “right to privacy” was nourished by both traditions of property and personal rights, even though these “were frequently in conflict through the nineteenth century in America” (123).

Thus, he says, legal scholars from roughly 1890-1920 “derived privacy from ‘the right of personal liberty'” (123). Others argued that “the peace and quiet of the home” and “the reputation of the individual” were in fact “property rights of the highest value” (123-24).

For more discussion of privacy in America and the law, see David Seipp, The Right to Privacy in American History, pp. 116-124 (1977-78).