Civil law’s influence on American common law: the appeal

By Kristopher A. Nelson

in

October 2011

700 words / 3 min.

Tweet

Share

In “Salamanders and Sons of God,” an article in The Many Legalities of Early America, Mary Sarah Bilder writes about the “Culture of Appeal in Early New England,” and situates the embrace of the right to appeal by New Englanders within the larger English and Roman legal tradition.

Please note that this post is from 2011. Evaluate with care and in light of later events.

In “Salamanders and Sons of God,” an article in The Many Legalities of Early America, Mary Sarah Bilder writes about the “Culture of Appeal in Early New England,” and situatesthe embrace of the right to appeal by New Englanders within the larger English and Roman legal tradition. English law in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was based on common law, a system that relied not on statute but rather on custom, and

in which pleas to the judiciary required addressing “reason”–“the faculty acquired by training that extracted some workable rules from a formless body of immemorial knowledge”–rather than appealing on the basis of what any ordinary person could claim was justice, equity or mercy (Bilder 51).

In the traditional common-law system, there were no appeals. There were various “writs“: the “writ of false judgment,” the “writ of attaint,” and the “writ of error,” but each of them involved horizontal appeals, not appeals to a higher authority. The common law was what judges, ruling on the basis of reason, thought it was, not what a king or higher authority said it was, so appealing to a higher authority made no sense. No new evidence or hearing was permitted on these writs, but only a review of the complex rules and procedures of the common law:

A party who felt that “manifest injustice” had occurred had to find justice by “proof of a technical error (verbal or procedural) in the previous trial” (52).

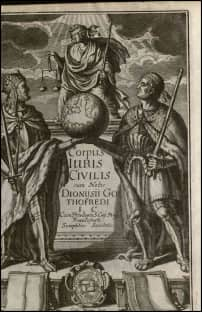

Alongside the common-law courts in England, another system of of equitable courts existed as well. This system grew out of the ecclesiastical courts, themselves developed in the tradition of the Justinian code–in other words, civil law. In this system, which handled cases “involving marriage and separation, probate and intestate estates, and slander and defamation,” among others, the goal was justice, and the procedures were more flexible (55). This system conducted appeals “in English, with depositions and interrogatories” and “was understood as a rehearing of both law and fact” (55). It drew on “an equitable theory of justice arising from medieval Roman canon law” (55). When Henry VIII replaced the Pope in England, he took on the Pope’s role as the ultimate appellate judge for courts of equity.

The appeal also took root in the corporate bodies of trading organizations. Formed by royal charter or patent, these trading corporations were authorized to maintain their own court systems, but with the right to appeal to the Crown guaranteed. Thus, Massachusetts and Virginia, both formed as corporations, were established with the right to appeal embedded into their systems. But the appeal remained even as the corporate structure disappeared, and was used as a means to establish and maintain a central authority.

Justice was important to Puritans. Thus, despite the historical connections to the hated Papacy, the Puritans embraced the “appeal to God” and its more secular variants as checks on injustice. Many “colonists thought equity was the point of the justice system,” and “colonial court systems did not separate equate courts like chancery from common-law courts” (68). (Interestingly, the combination of equity and common law meant that, for example, juries were required for appeals as well as for initial trials when the appeal involved matters of fact. )

In short then, the appeal represents the strong influence that the civil law has had on the common-law system. Today I often hear civil and common law described as opposite, distinctive, almost incommensurable systems, when in fact it appears that in actuality the modern American (and English, Australian, etc.) common law system is deeply indebted to the civil law tradition.